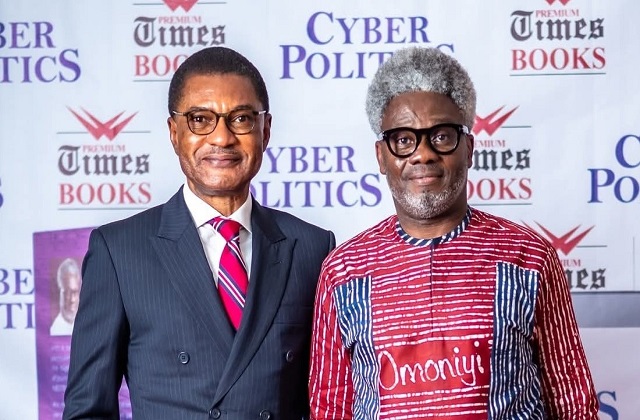

By Omoniyi Ibietan, Ph.D.

“Honourable Minister, where is the next port of call for you after the ministership?” I asked my principal in January 2007, as we commenced the final phase of his tenure at Radio House.

“Niyi, I am going back to school,” he responded with full metacommunication and paralinguistic, with a tincture of jocular appurtenances. Indeed, it came to pass. As soon as his tenure ended on May 29, 2007, he was off to the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University in the United States.

Before Harvard, he attended good schools and was properly educated in Nigeria, a persistent reader, humanist, statesman, decidedly dedicated patriot, impeccable dresser, an organically organised thought leader, with rare personal effectiveness that finds the first expression in the fact that he was never late to a meeting.

Okeifufe Frank Nnaemeka Nweke II, traditional leader of Ishi Ozalla, in Nkanu West Local Government Council of Enugu State, more popularly known as Frank Nweke Jr., (or still, FNJ as we call him in close circles), is a forthright, inimitable and phenomenal leader who continues to demonstrate that he is first and foremost human before becoming Igbo and Nigerian.

But the Igbo republicanism, egalitarianism, enterprise, and industry run in his blood to the last mile, including the distinctive devotion, painstakingness and resolute nature of Ishi Ozalla people, a community noted for extraordinary commitment to trading (distinctively in animal protein) and particularly agriculture. Ozalla’s soil is largely ‘stony and granitic’. So, farmers in Ozalla would count among the most painstaking, devotional species. That is the spirit FNJ brought to bear on national assignments as Minister.

Scion of the Nweke family, FNJ is pedigreed. His archetype was his father, the family’s patriarch, Igwe Frank Nweke I, Okeifufe Nakparu Ujo Nku I, of Ishi Ozalla. Born in Kano, raised across Nigeria, FNJ speaks Nigeria’s three major languages fluently, but his humanity extends to embrace people of languages he does not speak fluently.

A princely prince through and through, FNJ is not just lovely. He is kind, convivial, empathetic, and communicative. Though sometimes reticent, he could take no prisoners and can be as fiery as Sango. Let me instantiate, FNJ’s fury. One day in 2006, he came into my office, a space on the other side of his, which I shared with all my assistants in a conference room style. Please read the ergonomics of FNJ’s media office at the comment section.

That day of rage and fury, FNJ came into the office, and everyone rose to greet him as usual. He responded so economically. We all sensed trouble. After taking a bird’s view of the room to be sure we were in order, his eyes were still full of fury, almost ready to spit fire like Sango. Then, he muttered: “Niyi, come with me.” The first time he had said so in almost a year. So, I followed him like a disciple. He did not tell me where we were headed, but when the tour was over, I knew why he was furious.

He had complained a number of times about how some people deliberately held on to official files and delayed the turnaround time of works and routine activities, and he had issued a directive that turnaround time was 48 hours except there were objective grounds for delays. He was emphatic that such delays must be reported to the Permanent Secretary or the Minister’s Office. So, we visited some offices that were notorious for keeping files.

One after another, he barged in and asked: “Oga (Madam), tell me why files are delayed in your office unnecessarily.” You can imagine the panic and the speed with which affected officers rose from their seats. And before they could mutter a word, FNJ would end his mission with a warning: “Please, don’t let me come back here for the wrong reason.”

A cherished friend, brother, and mentor, my fortuitous meeting with FNJ at the National Youth Summit in May 2004, shortly after I defended my MA Dissertation at the University of Ibadan, was a turning point in my life. He provided the nudge I required to partake in the upturn unfolding in Nigeria at that time. He was Minister for Intergovernmental Affairs, Special Duties, and Youth Development.

He took special interest in my contribution at the summit, looked out for me at the syndicate sessions, and later requested my mobile number. He rang my line two days after I arrived back in Ibadan and requested that I return to Abuja to be part of the 7-man committee emplaced to draft a youth policy for Nigeria. By the time the committee work was completed, I was enlisted among the 5-man team that represented Nigeria at the International Youth Festival organised by the Arab Republic of Egypt in El-Arish.

For those who are very discerning and able to recall, youth administration politics since the beginning of Nigeria’s Fourth Republic took a decisive and intriguing turn. I was a member of one of the radical tendencies of the Nigerian student movement represented by the National Association of Nigerian Students (NANS). So, I was patently way off the curve of the emergent agency of the politically mainstreamed, supposedly liberal but sometimes sycophantic student/youth movements.

So, while I do not know how other members of the team to Egypt made the list, I knew I was FNJ’s nominee. But I recalled a familiar face in the Nigerian team, Dr. Umar Tanko Yakasai, a hitherto tenacious Northern star in NANS, who was studying medicine at the University of Maiduguri in the truculent days of Abacha. Umar had become the national secretary of the National Youth Council of Nigeria (NYCN).

We quickly bonded and formed a coded ‘minority group’ on the road to Egypt, an alliance that impacted the report of the conference we submitted to the Ministry after the Egypt journey. FNJ did not only accept our report, he implemented it with speed. A central element of that report was the imperative of inclusiveness and expanding the geography of the democratic space for youth participation in governance through conscious self-activity; making entrepreneurship a component of education curricula, immersion of young people in the didactic experience of the emerging digital culture; and finally, the centrality of cultural intelligence in leadership.

As we left Egypt and headed to the ‘promised land’, I continued to relate with FNJ and I contacted him later that year when the organisers of the International Student Festival in Norway accepted my proposal to speak at the forum. He was not only excited about the information; he personally sponsored my trip. My relational exchanges with FNJ grew in leaps and bounds, and we discussed ideas frequently. Perhaps I was an aide incognito until December 2005 when I visited him at Radio House after an evening lecture.

I was an instructor at the International Institute of Journalism, and he had become the Minister of Information and National Orientation (later Information and Communication). I visited him in the company of my brother and comrade, High Chief Ezenwa Nwagwu, whose office was in the same facility where I was teaching. During my next visit to FNJ, we had series and fragments of conversations and then lunched in his inner office.

Thereafter, we relocated to the main office and continued the conversation. His spiffy jacket hung appropriately on the coat tree hanger made of polished steel and leather; his tie readjusted to business style, and his sleeves rolled up the Obama way. As he took his seat, he asked me to sit too. Then, in a voice that took oxygen from both spiritual and temporal realms unequivocally immersed in serious tenor, he uttered: “Niyi, you are coming here as my Special Assistant on Media.”

He did not wait for a response. Then, he called one of his secretaries: “Tony!” The man heard him, came into his office with his pen and paper to join us. “Niyi is going to join us here as my SA on Media. Do a letter to the President through the Secretary to the Government of the Federation and request special approval.” Chief Ufot Ekaette was the SGF at that time. I requested time to consult, and he refused. He then recalled my contribution at the Women Development Centre, venue of the summit in 2004, where he first met me, and said his offer had provided a platform for me to make my views to reflect in government policies.

…….to be continued

**Dr. Omoniyi Ibietan was Special Assistant on Media to then Minister of Information, Mr. Frank Nweke Jnr.